Football is one of America's greatest pastimes. In fact, most people have fond memories regarding football, even if they don't even like the sport. Whether it's watching Thanksgiving games with the family, or going to practice in highschool, people have a deep connection to the sport. It's as if football is eternal.

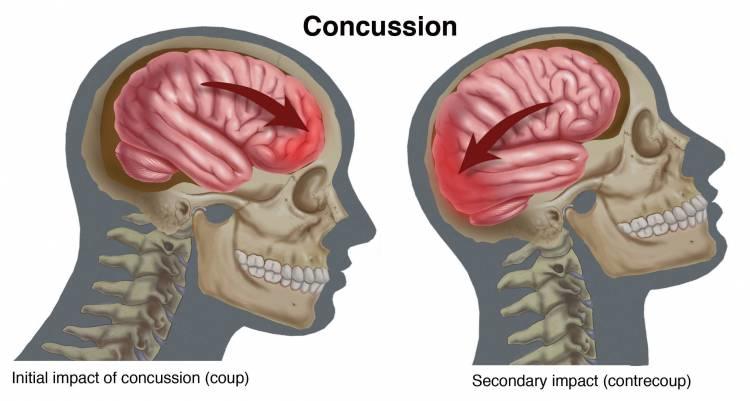

Over the past decade more and more research has gone into one of football's biggest problems: The hard hits and their impact on the players. What is known as Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) has grown as a greater and greater concern for players and the fans. CTE is an Alzheimer's-like disease caused by trauma to the head.

Scientists are frantic to figure out just exactly how CTE works, and why it affects some players so greatly compared to others. While we know that CTE is a problem, players continue to play and take hits, so time is of the essence. Recent research points to the key lying in genetics.

While repeated strikes to the head isn't good for anyone, we've seen that some people are affected much more by CTE than others. Research at Boston University's CTE Center have done research to find that there is a variant of a specific gene, the TMEM106B gene, which may be the cause of more severe forms of CTE. Dr. Jesse Mez, an assistant professor of neurology at Boston University's School of Medicine had this to say: Among people who have CTE, people with this [genetic] variation are 2.56 times more likely to develop dementia."

The research findings are still in their early stages, and Dr. Jesse Mez sees this more as a lgreat starting point: "It helps us better understand biologically, mechanistically, what is going on in the brain in CTE. In understanding the mechanism and in identifying this genetic risk factor, we have new potential targets to develop therapies."

The research may be in such early stages that some consider it too early to discuss with any serious. For example, Dr. Sam Gandy from the Center for Cognitive Health at Mount Sinai in New York feels that there are other genes that could be involved with the disease that the study ignored. Another pathologist, Dr. bennet Omalu said it was too early as well, stating, "We need to tread carefully. The study shows that the gene may be associated with reduced risk for CTE, but CTE is a polymorphous and polyphenotypic and polygenetic disease, [and] focusing on one gene, which may reduce risk, may be a stretch."

While these results may be too early to call, Dr. Mez and his team are still looking into other factors and genes. The plan is to put their findings into consideration, but to keep studying as well.

While the findings can be tenuous this early in the process, that doesn't mean they don't have value and won't be used to further research. A professor of neurosurgery at University of California, San Francisco, Dr. Geoff Manley, thinks that this research is a good step. "This research, while early, suggest there may be some genetic risk factors. However, there was no difference between those with and without CTE. The TMEM106B gene has also been associated with frontotemporal dementia, suggesting potential overlap with a number of neurodegenerative diseases."

Dr. Mez ultimately sees value in this research due to seeing patients with similar exposure to head-trauma suffering different levels of CTE. "We see a lot of former athletes who have similar levels of exposure. Two football players in college, who played eight to 10 years. Late in life, one of them develops severe disease, and the other might be mildly impaired. I think it's of value to understand that difference, and this finding starts to explain these types of differences."