There’s no doubt that Las Vegas is a vibrant, exciting city that draws millions from around the world. Whether your interests gravitate towards gambling, entertainment or food, it’s a city that is only too glad to supply your wants. One might say that plagues of tourists descend upon the town.

But even as modern day locusts in Hawaiian shirts reign, their insect forebears continue on as they always have, periodically erupting in spectacular gatherings that force us humans to sit up and take notice. Be it love bugs, or dragonflies, or ants, those bugs adore getting together for some fun.

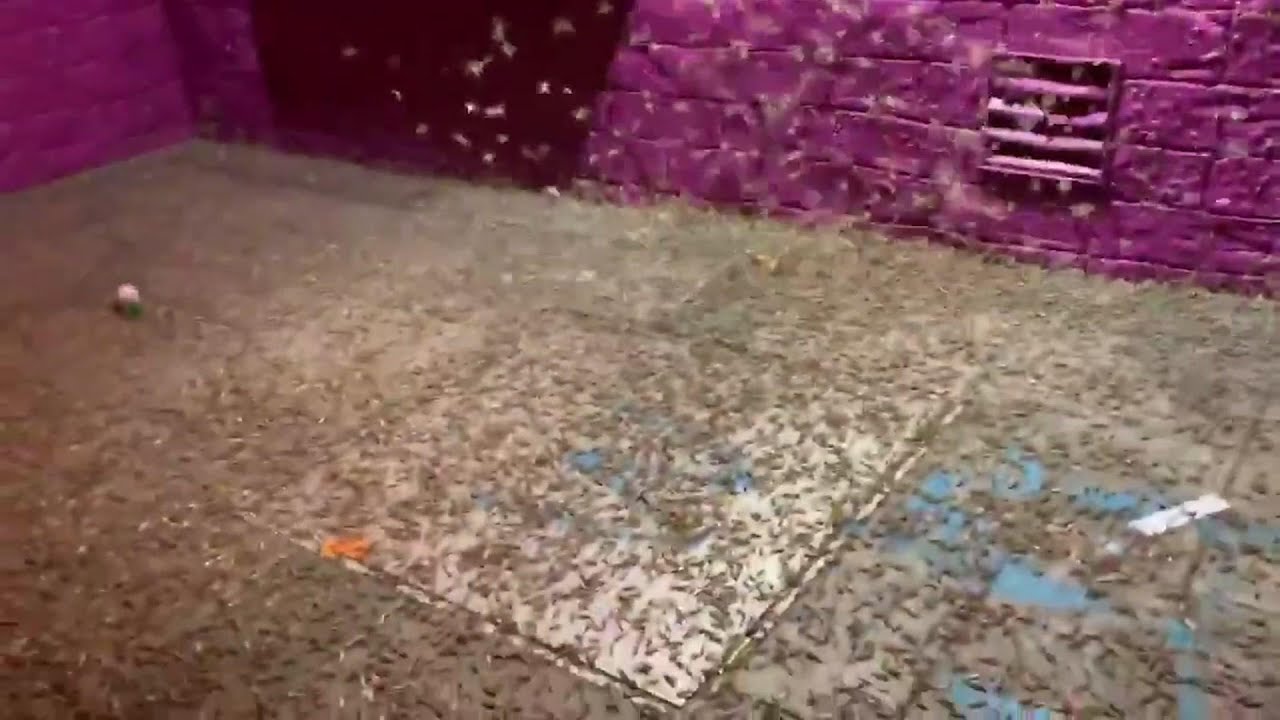

So it was perhaps no surprise, given how much fate had been tempted for so long when enormous numbers of grasshoppers decided to hit Sin City and the surrounding environs of southern Nevada in 2019 for what has been called by residents “the great grasshopper invasion of 2019” ever since.

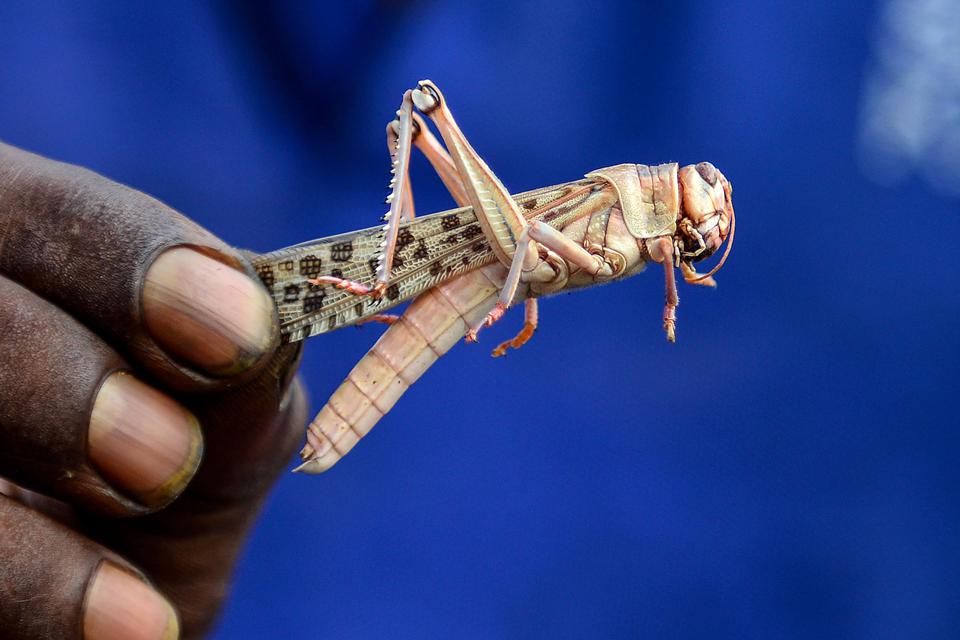

It was in July of 2019 that the swarms of pallid-winged grasshoppers, whose proper scientific name is Trimerotropis Pallidipennis, appeared in the Clark County area—and they did so in such great volume that regional weather radar captured them. That data was used by Elske Tielens of the University of Oklahoma to provide the understanding that we have of the incident today.

Her team of researchers at the university, after compiling and analyzing the numbers from some two and a half months of recorded weather station data, found that it was in both June and July of that year that a peak total of nearly 46 million of the grasshoppers were concentrated in the Las Vegas area (although understandably only estimates are possible short of significant buy-in from the grasshoppers in completing a census form)

The study was able not only to as accurately as possible put the size and duration of the gathering of grasshoppers at the above numbers, but to reach conclusions about their behavior during it and therefore what its likely causes were so that we might better be able to deal with insects both beneficial and deleterious.

It was found by the researchers that the grasshoppers tended to alight on ground where significant vegetation was located during daylight hours, inviting the inference that the insects were motivated by a desire for food and potentially for shelter as well. But at night, found the researchers, the major motive of the grasshoppers came to the fore. It was at that time each day that they took to the sky and gravitated towards urban areas that were brightly lit.

The authors of the University of Oklahoma study say that it further contributes evidence to substantiate theories about the existence of artificial lighting at night influencing and affecting the behavior of animals.

The data could cause changes in public policy where the placing, intensity and color of such man-made lighting is concerned, as has already happened previously in, for example, locales where white lights are mistaken by sea turtles for the moon they use to navigate as they migrate. For that reason local governments require that porch lights be altered to not affect animal life, and while an equal level of concern for the survival of grasshoppers may not be necessary, similar action might be taken in Nevada and other affected areas to avoid the adverse effect of repeat incidents of the infamous 2019 invasion.