It is in the nature of human beings that, due to the enormous complexity of daily life, many mental tasks are essentially handled by an autopilot: a standard operating procedure that unthinkingly, successfully completes the majority of tasks entrusted to it. A human employee with that success rate is exemplary.

A minority of tasks ultimately will require conscious effort, and mental energy must be saved for that. It would be wasted on low-stakes events such as replying to a movie theater employee who has just sold us a ticket. Thus, you say “you too” in answer to “enjoy your movie”.

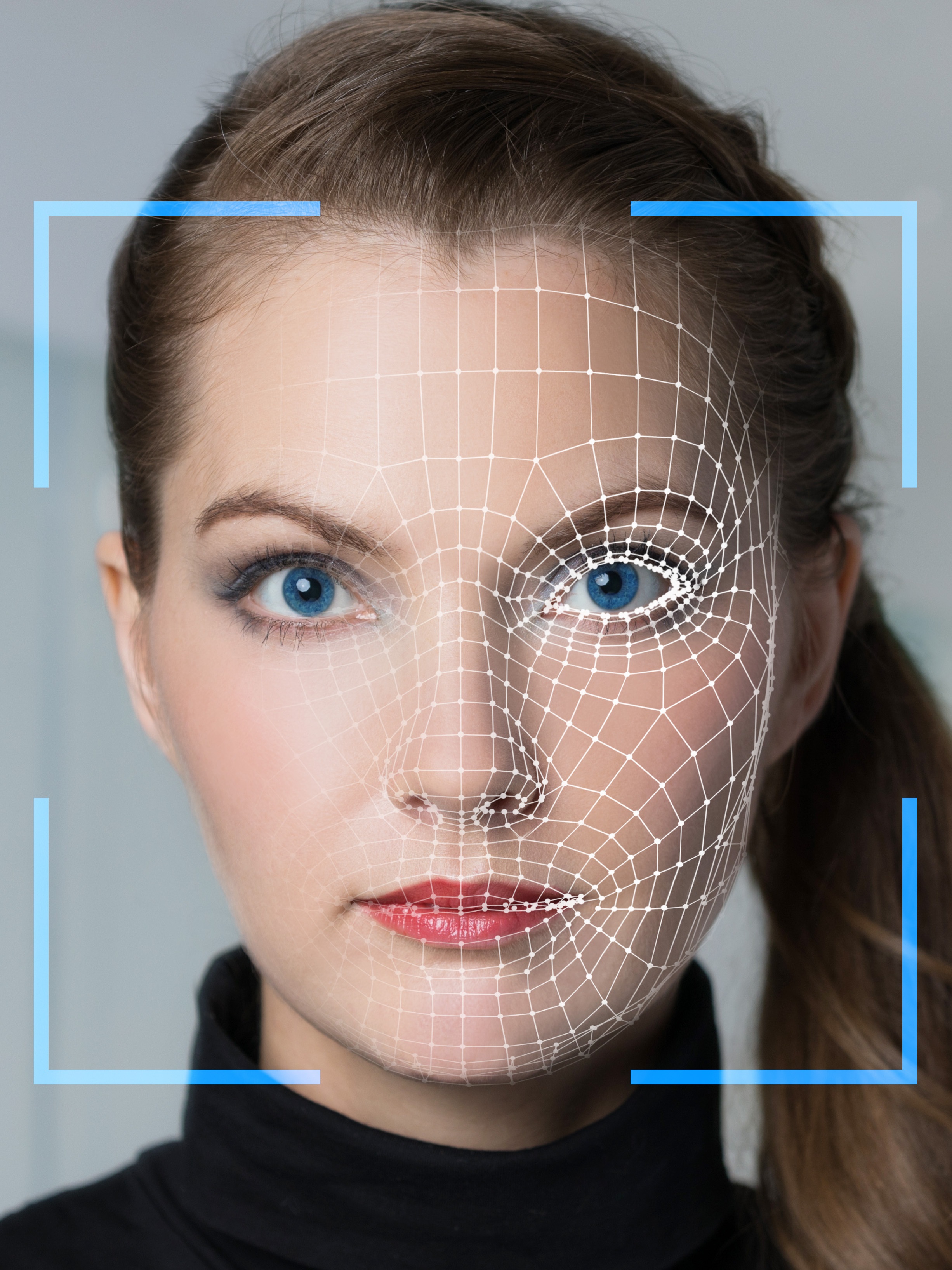

The net result is huge efficiency at the cost of occasional amusing mistakes, and this is seen as much in the very primal human task of identifying faces around us as a precursor to identifying what may be a threat, or may be a friend. Mostly you’re right, sometimes wrong.

Historically the manner in which the human brain picks out faces visually, and towards what end, has not been well understood beyond the anecdotal information that you yourself likely already have, from incidents such as seeing what looks like a smiley face on a tostada. We now know far more about the motivation to see faces behind this, and how it is achieved.

Professor David Alais is the leader of a study on the subject at the University of Sydney’s School of Psychology, and according to Professor Alais the benefits of seeing faces everywhere easily are obvious and huge. They are so big that little benefit is lost from a very haphazard system that results in a relatively high number of false positives. Otherwise, a more efficient and energy-intensive process would have resulted from evolution.

Professor Alais’ most recent study was designed to ascertain whether, upon realizing that a possible face is merely a face-like arrangement of objects that resemble the placement of eyes, a mouth, a nose and other features, further effort is nonetheless expended to ascertain an expression (and its meaning). Subjects were shown a series of faces, some real and others not, and assessed as to whether they did in fact continue to search known false faces for emotional meaning.

These findings follow on those of a previous study which found that one’s analysis of a face tends to be heavily influenced by the conclusions drawn about a just-seen other face. And it would stand to reason that if the human brain expects to see a number of faces in succession, most faces would be the same.

The study from Alais’ team at the University of Sydney confirms the unconscious search for efficiency by the human brain even at the cost of occasional mistakes, most of which result in minimal waste and perhaps even some level of joy from the awareness of a harmless error in judgement.

And that joy is likely also partly from the inescapable nature of human beings as being heavily social: not merely searching for faces around them in order to rule them out as threats, but doing so because a face may mean another person or living thing that ultimately represents the positive force of like beings and thus community. So if you see a face in the chance arrangement of a banana and a couple oranges on a plate, now you know better why that is.